What are telomeres? Can they help us live longer? What can we do to protect them?

- What are telomeres?

- Why do telomeres matter?

- What is the evidence for their importance?

- What can we do to protect our telomeres?

- Conclusions

What are telomeres?

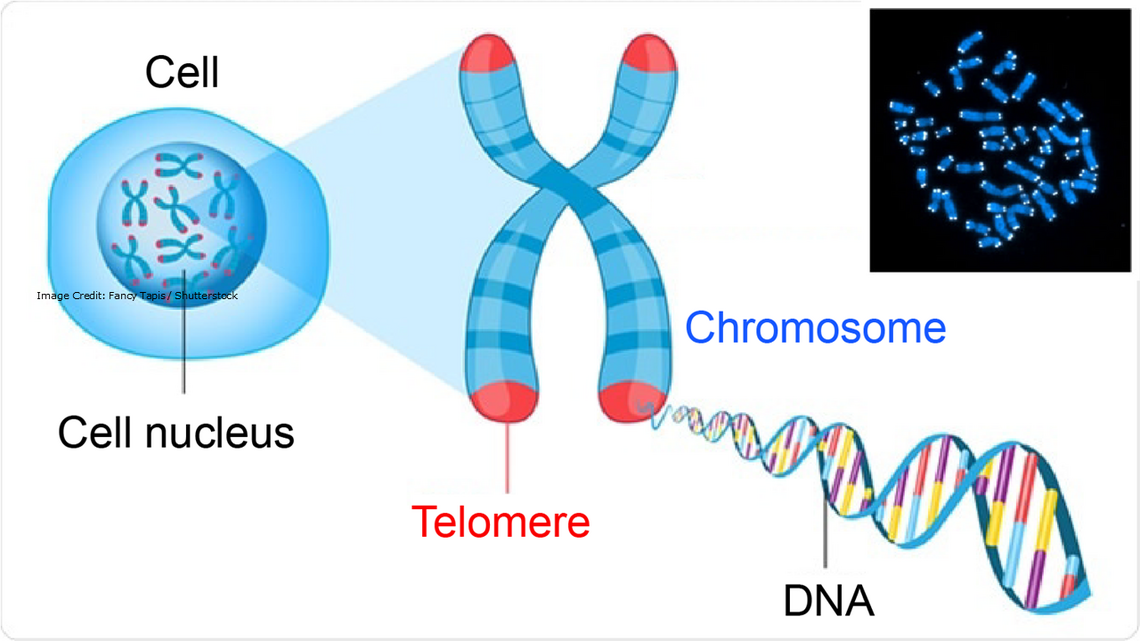

Telomeres are part of our genome (our genetic make-up) located at the end of the chromosomes in our cells.

Telomeres form a cap, like the plastic tip on shoelaces, which protects our DNA. The length of telomeres is shortened by age, by many age-related illnesses and by cancer. Their length depends on the enzyme telomerase which repairs them and maintains their length during successive rounds of cell division.

Why do telomeres matter?

Telomeres protect the two ends of our chromosomes therefore they play a vital role in protecting our genetic make-up. However, every time a cell divides, part of the telomere is chopped off from the chromosome’s end, and the telomere gets shorter. When a telomere becomes too short, it can no longer protect our genome, the cell can no longer divide, and it becomes inactive or "senescent" and dies.

Telomere-shortening is a risk factor for numerous diseases and may be a general biomarker of ageing.

|

There seems to be a clear association between the length of our telomeres and our health and longevity. |

What is the evidence for their importance?

The link between shorter telomeres and increased illness and shorter life in people was first reported in a study published in The Lancet in 2003. Individuals aged over 60 were recruited and divided into two groups according to the length of the telomeres in their blood cells. People who had shorter telomeres were found to die earlier due to higher mortality rates from heart disease and infectious diseases. Conversely, those who had longer telomeres at the beginning of the study lived an average of five years longer than those with shorter telomeres.

Several other indications that telomere length is a good predictor of longevity have been reported. For example, a 2007 study found that in elderly twins, the twin with shorter telomeres was about three times more likely to die first. More recently, in 2014, a systematic review of published research involving some 36,000 participants found that some studies suggest telomeres are longer in women than men.

However, there is some debate as to whether shorter telomeres cause illness and an early death or are simply a useful indicator of vulnerability to illness and an early death. Whichever the case, it seems to be in our interests to protect the length of our telomeres for as long as possible.

Individual telomere-testing is still in its infancy and isn’t yet available on the NHS. So, for the moment, the focus needs to be on what we can do to protect our telomeres, based on the research published.

What can we do to protect our telomeres?

The good news is that some research suggests that a healthy lifestyle seems to help protect our telomeres. Our lifestyle choices are important:

- Avoid smoking and air pollution

- Reduce stress

- Eat a healthy diet and maintain a healthy weight

- Exercise regularly

1. Avoid smoking and air pollution

A 2005 study in The Lancet found the telomeres in the white blood cells of obese women to be shorter than those in lean women of the same age. The researchers calculated this was equivalent to reducing life expectancy by nearly nine years. The same study also found that the more women smoked, the shorter their telomeres were.

While this was a sizeable study, reported in a reputable journal, we should note that a larger and more recent study (published in 2014) reached a different conclusion: that lifestyle factors such as smoking, increased body weight and physical inactivity were not associated with shorter telomere length.

However, a small US study, reported at a conference in 2015, found that pregnant mothers’ smoking habits appeared to have a knock-on effect on the length of their babies’ telomeres. More substantial research is needed to confirm this finding, but it suggests that what happens early in life., including mothers smoking, can make a difference to telomere length later in life.

A systematic review of 25 studies, with 12,058 participants, reported that most of the studies support the association of shorter telomere length with air pollution, suggesting another factor that may influence our telomeres.

2. Reduce stress

Stress has also been identified as a risk factor leading to shorter telomeres.

A small, initial study is backed up by other research, which suggests that telomere length is influenced by what happens in the womb, including the impact of cumulative psychological stress that pregnant mothers are subject to.

A 2016 systematic review using meta-analysis looked at the association between measures of short-term stress, psychological stress and telomere length. The review analysed the data from nearly 9,000 participants, using gender, life-stress exposure, and psychological stress as potential co-founders. Increased psychological stress was associated with a very small decrease in telomere length (adjusting for age). When using validated measures of psychological stress, this relationship was similar between genders and within studies. It was marginally (but not significantly) stronger among participants with exposure to stress. Although the effect was small it was statistically significant.

In addition, this study considered short term stress. The literature suggests that long-term chronic stress may have a greater cumulative effect on the length of telomeres. The study recommended that future research should use longitudinal, multidimensional models of stress to investigate shortening of telomere length.

3. Eat a healthy diet and maintain a healthy weight

A 2011 review of lifestyle factors that might affect telomere length concluded that ‘a better choice of diet and activities has great potential to reduce the rate of telomere shortening. The review suggested that better lifestyle choices could at least prevent excessive telomere attrition, leading to a delayed onset of age-associated diseases and thus an increased lifespan.

A study of 2,284 women in the US, published in 2010, found that eating dietary fibre had a modest but positive effect on telomere length. Conversely, Omega-6 fatty acids, found for instance in vegetable oils, had a modest but negative effect on telomere length. As we identify elsewhere on the Age Watch website we need some Omega-6 in our diets (but not too much) and it needs to be balanced by Omega-3, which is found in fatty fish, flax seed, soy and walnuts. https://www.agewatch.net/diet/good-fats-and-bad-fats/

Interestingly, a study of 608 outpatients with stable coronary heart disease in California, also published in 2010, found that a diet containing antioxidant Omega-3 fatty acids was associated with a reduced rate of telomere shortening. This suggests that more Omega-3 (fatty fish, flax seed, soy and walnuts) and less Omega-6 (vegetable oils) in our diet may be helpful for maintaining telomere length.

A major European study of more than 2,000 women found that ‘a higher maternal BMI with excessive weight gain during pregnancy resulted in shorter telomere length in the offspring’. This effect was observed both at birth and later in their adult children.

These studies have been conducted with women rather than men. However, studies that have included both men and women have tended to find that losing weight and physical activity is also beneficial for telomeres in men.

4. Exercise regularly

Exercise has also been suggested to enhance the length of telomeres. In a recent systematic review (2019) 11 studies met the criteria for the meta-analysis which looked at the data from 19,292 participants. The influence of daily exercise on telomere length was assessed in two groups of volunteers: one that took robust exercise and the other that took moderate exercise. The results were compared with an inactive group of volunteers. Longer telomere length was associated with the physically more active groups. Telomere length of the participants who took robust exercise was greater than those who took moderate exercise. There was no association between the length of telomere and gender, and no statistically significant finding in the elderly participants.

A German study of endurance exercise – such as running, swimming, cross-country skiing and cycling – reported that a single 45-minute jog enhanced telomerase activity two- to three-fold for several hours after stopping the exercise, thus ‘improving healthy aging’. A traditional weight-machine circuit had little to no effect on telomerase activity. The enzyme telomerase repairs telomeres and maintains their length.

The study found that the higher the heart rate when doing endurance exercise, the greater the increase in telomerase production, whereas resistance (circuit) training did not induce telomerase production. Resistance training, however, was the key to maintaining muscle and bone as we age.

Training exercises may prevent comorbidities associated with obesity and may also prevent the shortening of telomeres induced by obesity. Furthermore, abdominal fat and size of waistline were both negatively related to telomere length.

Conclusions

- Telomeres have an important protective role inside our bodies, helping to protect the DNA within our chromosomes.

- Shorter telomeres are associated with a greater risk of illness and an earlier death i.e. faster biological ageing.

- There are two factors affecting the length of our telomeres that we can’t control: ageing and genetics.

- However, we can choose to follow a healthy lifestyle, by not smoking; taking regular exercise; maintaining a healthy weight; eating a healthy diet (containing dietary fibre and Omega-3 in particular); getting enough sleep and avoiding excessive, long-term stress.

- Most (although not all) research published so far suggests that a healthy lifestyle helps protect our telomeres, with positive results for our health and for how long we are likely to live.

__________________________

Other relevant articles on the Age Watch website:

- Fitness: Exercise and live longer

- Fitness: Keeping fit – Why bother?

- Fitness: Can fitness compensate if you’re overweight?

- Living longer: Look after your body

- Living longer: Adding years to your life, and life to years

- Age and gender: Women and smoking

- Tackling obesity: Preventing obesity

Reviewed and updated August 2020. Next review, July 2024.